Food for Thought Blog

IAP2 Tech Panel Discusses Virtual Engagement

(This is a reprint of a blog post contributed to PublicInput.com)

PublicInput had the pleasure of joining other public engagement tech companies on a virtual panel at the 2021 IAP2 North America Conference. Sharing our experiences, insights and predictions surrounding virtual public engagement with our colleagues and practitioners is always an enjoyable and productive experience.

Dr. Kristin Williams with PublicInput, joined Aaron Bernard of Spatial Media, Ward Ferguson of Jambo and Joseph Thornley, of 76Engage. Aaron’s Spatial Media colleague, Rohan Aurora, moderated the panel that addressed three questions concerning the impact of the pandemic on public engagement, adapting new technologies to existing engagement practices, and future predictions.

Below is a summary of the exchange that ensued.

Question #1 – The Pandemic:

What were the impacts and trends that emerged in engagement?

This was a retrospective question to explore lessons learned. A general observation from the panelists addressed how unprepared technologically and procedurally many public institutions were to respond when conventional, in-person engagement and deliberations were halted. However, everyone acknowledged and credited local governing bodies for their quick actions and creativity, along with a seasoned group of public engagement practitioners to respond and adapt to the dire circumstances and the need for continuity of our public institutions.

Panelists noted the presence of new government staff who not only attended the virtual public meetings (VPMs) but were also running them on behalf of their organizations: the CIO or IT department. Their chief role was to ensure virtual meetings would be convened with as little disruption as possible.

The panelists cited their own experience working with customers and feedback from public engagement practitioners about the challenges to integrating technology platforms in their proceedings, however, there is general acceptance of their benefits for using virtual public meetings in the future and interest in blending them with in-person deliberations currently and to continue after the pandemic subsides. These views were also noted in a study by Engaging Local Government Leaders (ELGL) and others that found support to continue the use of virtual meetings and mirrors the thoughts of PublicInput.

Data collected over the past 18 months demonstrate VPMs are having a positive impact on public engagement. And with the resurgence of the COVID Delta variant governments are not in a hurry to cast aside their role in governing and democracy. VPMs provide a sustainable option for increasing public participation and offer jurisdictions an effective input and feedback tool to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion in their deliberations.

Providing a “win-win-win-win” scenario benefiting public engagement practitioners, governing bodies, govtech solution providers, and residents, the panelists were optimistic about wider adoption and a bright future for VPMs.

Question #2 – Adaptation:

What are people doing today that could be improved with tech?

The moderator asked panelists to share advice with the attendees from what they have learned and are seeing in virtual public engagement practices. Panelists suggested that 2020 was a tumultuous year for public participation due to the pandemic, the social injustice protests surrounding police reforms and a divisive, polarized presidential election followed.

“We are at a pivotal point in the relationship between the government and constituents,” noted Dr. Williams. There was mutual agreement that trust in government and trust in society had suffered and one way to help rebuild trust was through greater transparency, inclusive participation and accountability. And solutions to address those challenges will have to come through greater use of technology to encourage and facilitate greater collaboration between government and residents.

Panelists also discussed the benefits and potential liabilities for governments using social networks as public engagement platforms versus the government’s own and managed engagement platform. There was some disagreement on this topic between PublicInput’s Williams and Jambo’s Thornley. Thornley argued against their use as it provides private social networks with free data from the public. Williams suggested there were some roles for social networks in public engagement as communication and information providers. Both panelists agreed to continue the conversation beyond the IAP2 session as this is an important, unresolved topic surrounding data ownership, security, and privacy.

Question #3 – The Future:

What does the future look like for engagement and technology?

The moderator suggested the panelists address this hypothetical question by identifying social and technological trends that have and could impact the future of public engagement. As an example, the moderator asked how tech support might foster or potentially present challenges to engagement practices.

There was total agreement among the panelists that a new era of public engagement and representative democracy is emerging thanks in part to a changing culture and enabling technologies. This includes new models for how governance and public engagement are administered and how to use media tools to rebuild public governance.

The panelists returned to the experiences of local governments during the pandemic and the use of VPMs and their potential to be at the center of public participation. This discussion included trending topics in public engagement around growing interest in blended, or hybrid models of public engagement that combine conventional, in-person methods with virtual models.

Panelists suggested as the new technologies become more ubiquitous and more user-friendly, the heavy emphasis on CIOs and IT will fade with the administration of these platforms directed by staff who traditionally played a role in public engagement.

Finally, panelists cited the opportunity to increase and expand the use of virtual public engagement to opportunities beyond council meetings and public project feedback to tap into the knowledge of their residents for contributions to solutions for the many socio-economic challenges local governments and communities are facing.

Public Engagement Effectiveness

(This is a reprint of a blog post contributed to PublicInput.com)

Enterprise Public Engagement

Applying enterprise approaches to public engagement helps government increase input and feedback for better decision-making, inclusion, and efficiency.

The IBM Center for The Business of Government connects research to practice in helping to improve government and to assist public sector executives and managers in addressing real-world problems with practical ideas and original thinking to improve government. The“Seven Drivers Transforming Government” is the culmination of research with current and former government leaders that identifies seven drivers for transforming government in the years to come.

PublicInput is applying a selection of those drivers to interpreting the future of one of the government’s most important success components: public engagement.

Effectiveness

IBM Center for The Business of Government

Applying enterprise approaches to achieve better outcomes, operational efficiency and a leaner government.

Approaches to Engagement

When asked for examples of public engagement, many people may suggest a town hall or council meeting where members of the public are allotted a brief opportunity to provide public comments to their elected officials. Others may point to government initiatives around transportation or environmental projects where governments seek input or feedback from impacted residents.

Few people, if any, suggest an example of public engagement as a 24/7/365 service between the government and their constituents. On the surface, daily engagement sounds like a pretty massive undertaking. Engagement practitioners often wonder, can something like this be accomplished and what benefits can be realized for a government and a community engaged in on-demand collaboration around important policy issues.

The answer is a government with the ongoing goal of being more effective, both in terms of its operations and results.

Effectiveness

Effectivity has been demonstrated through the use of technology across government agencies –known as the adoption of enterprise solutions– to deliver mission-support services seamlessly across program and organizational boundaries.

The Future of Performance

IBM Center for The Business of Government

. . . the future of government performance relies not simply on greater efficiency, but also on increasing capacity to work effectively

How does this apply to public engagement?

We saw firsthand at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic the critical challenge for state and local agencies to effectively use technology to continue their deliberations with public officials and the community. To continue public meetings in many jurisdictions, it took emergency executive orders, supporting legislation, and a corps of talented and hard-working CIOs and IT departments across the nation. Not only was the government less efficient in carrying out the basic function of public engagement, it was also noted among many jurisdictions and governing bodies as an ineffective way to inform constituents and to solicit input on public issues.

As the pandemic continued, most governing bodies adopted some form of information and/or communication technologies to continue meetings and public engagement, even without the efficiency or effectiveness required or desired. Today, a new era of public engagement and representative democracy is emerging through the use of dedicated public engagement technology platforms.

From these platforms, governments are realizing the benefits of blending virtual and conventional approaches to public engagement that increase and diversify participation. Data collected through the use of new public engagement models to organize and centralize public governance are creating more effective processes that can be realized across multiple departments.

Positive, Significant, & Lasting Change

IBM Center for The Business of Government

To achieve positive, significant, and lasting change, government leaders must focus on sound implementation. The focus on implementation involves the meaningful integration of operations across agencies via an enterprise approach.

24/7/365 Engagement

Governments need to consider what an enterprise approach to public engagement could look like with a 24/7/365 public engagement process. It will take a rethinking of how we use technology and how we define public engagement.

It will require the government and the public to change the narrative when it comes to public engagement. Instead of being selective where public participation or comments are sought, the government should be engaging the public on issues in every department every day. This cannot be accomplished without the use of technology solutions. Fortunately, we have the technology capable of enterprise deployment.

Governments must also consider how they can be more effective through more engagement. There is a vast ocean of knowledge among the residents in a community. Many who possess skills and expertise about challenges the government faces every day surrounding public policies would offer their input or feedback if given the right mechanism to contribute to it.

At PublicInput, we agree with those thought leaders who advocate governments should constantly be thinking about how they can tap into the community’s energy and enthusiasm and leverage that with public work being performed by the government on their behalf.

Enterprise Government

IBM Center for The Business of Government

. . . enterprise government focuses on mission support and emphasizes streamlining and integration of administrative services, as well as processes and functions that share common elements.

Public engagement can be a shared service —government-wide or department-wide– as a system that can be standardized, produced, and delivered, aligning enterprise approaches with problem-solving. That is, public engagement should look and operate the same across all government sectors and agencies offering governments a centralized, organized, managed, and reported system made more efficient through an enterprise solution.

Government Transformation

IBM Center for the Business of Government

Enterprise approaches that leverage modern management and technology systems and practices can enable progress across the public sector. The evolution of enterprise government can give fresh momentum to improving effectiveness and driving transformation in government.

Adding “engagement” to public administration along with the basic framework of economy, efficiency, and effectiveness is a principal way of practicing the work of governance with more inclusion and equity creating more informed decision-making.

Virtual Meetings & State Legislatures

(This is a reprint of a blog post contributed to PublicInput.com)

More state legislatures are enabling virtual public meetings as an option for deliberations and public engagement.

Historically, government officials have been required to meet in person to deliberate about the public’s business. This has been particularly true for meetings that included constituents and their elected representatives. Some states even have laws requiring officials to attend meetings in person.

Face-to-face meetings between elected officials and the public are important.

This is because elected officials can’t ignore people that are right in front of them talking about a problem or a policy. It also helps them put a “face” to a certain issue or law. The public’s physical presence at a meeting can be very impactful when making decisions and could affect the outcome.

Times and technology have changed and public attendance at council meetings or committee meetings usually represents those who have a strong opinion for or against the issue that is being debated and may not represent the voice of the whole community.

The Pursuit of Alternative Means

In March 2020 as the COVID-19 virus became a pandemic, state and local governments were forced to shutter their buildings and halt their in-person proceedings. Alternative means had to be pursued to conduct the public’s business and for the continuation of governance.

For years, the public has had options to view or listen to their governing bodies’ proceedings electronically, whether online, televised, or by radio and officials were physically present in those proceedings. Now, the elected and the electorate would need to segregate from each other and conduct their meetings virtually. Yet, some states had laws that required meetings of public bodies to have the officials present which prevented them from attending virtually.

With the growing pandemic, states had to act fast to enable the government to continue to operate and in a way that would not violate their open government laws surrounding access, participation, and transparency of public meetings.

Executive orders became the norm in most states to enable their governments to continue operations, including holding virtual proceedings. Those emergency orders, however, had deadlines so it was up to state legislatures in those states that restricted virtual attendance to create formal alternatives for convening public meetings.

Fast forward to the summer of 2021

With a year and a half of a continuing (and resurging) pandemic, along with 18 months of positive data about the effectiveness of virtual public meetings (VPM), decisions by state and local governments to meet virtually have taken hold across the nation on whether or not there were legal restrictions preventing them. Today, VPMs as an alternative or complement to in-person meetings are launching a new era of public engagement for governments and for residents.

Recall that not all states have laws requiring in-person attendance by officials that prevent VPMs and therefore do not require legislative action to approve their use. Wyoming is a good example of a state that switched to VPMs over the last year and a half, including hybrid models, to ensure continuity of services and decision-making along with public outreach.

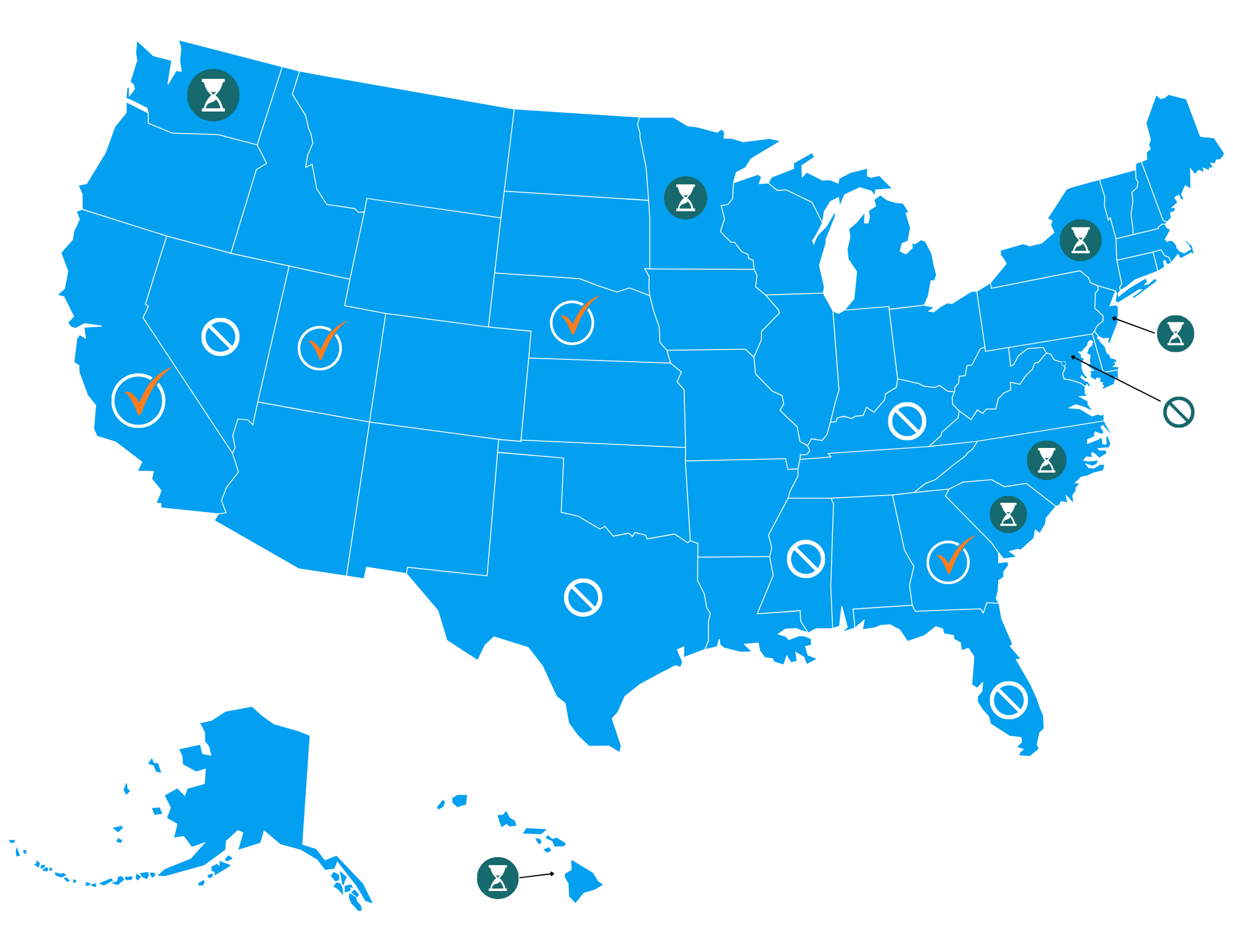

For those states that either required officials’ in-person attendance or wanted to revise legislation to ensure VPMs were included in their public meeting requirements, 17 states had bills filed over the last year that included language pertaining to VPMs, according to BillTrack50, a free research and tracking service of state and federal legislation and legislators from LegiNation, Inc.,

So far, four of the 17 states have signed and enacted legislation to support VPMs (California, Georgia, Nebraska and Utah), while seven are still in committees or have been approved by one chamber and crossed-over to the other. These states include Hawaii, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina and Washington. Bills addressing VPMs in six states died in committee or failed on the floor: Florida, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Nevada and Texas.

A New Way to Govern

With or without needed changes to laws to enable VPMs across state and local jurisdictions, many public officials and residents are realizing the benefits along with the challenges of adjusting to VPMs and hybrid models that blend VPMs with in-person meetings. Residents are enjoying the ease and convenience to learn about and engage their public officials without the challenges to their schedules including traveling to a meeting for whatever reason they may have.

Public officials are seeing the ranks of public participation swell and increased diversity among attendees. Key challenges facing public bodies such as inclusion to hear from more voices in the community are being facilitated using VPMs. The public’s personal preferences surrounding communicating and sharing information with public officials are being met and with greater ease. That helps build more trust between public officials and residents.

Whether out of necessity or in response to a disaster, state and local governments and their constituents are finding VPMs provide a new and welcoming way for governing and advancing democracy in their jurisdictions.

Re-Examining Public Meetings

(This is a reprint of a blog post contributed to PublicInput.com)

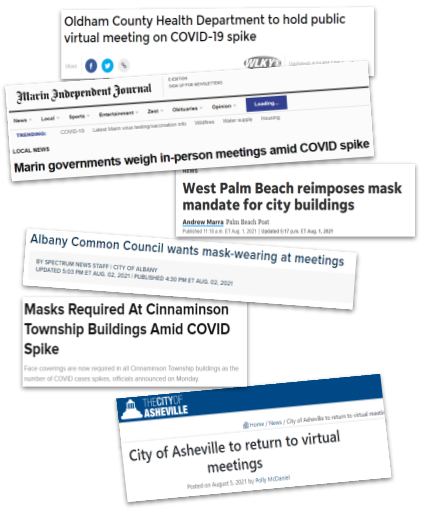

Local jurisdictions rethink public meetings amid spikes in COVID-19 cases

Headlines from the pandemic outbreak in 2020? No, these are announcements local governments have made in recent weeks as new cases of COVID-19 infections are exceeding totals recorded in 2020.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are reporting new outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infections, including COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infection, associated with large public gatherings. Local governments are faced with a critical challenge regarding in-person public meetings in the midst of a resurgence in the pandemic as many jurisdictions returned to in-person deliberations

A Re-examination of Priorities

After vaccines became available and inoculations of U.S. residents increased with lower cases of COVID-19 infections being reported, local governments planned a return to in-person meetings. However, after more than a year of virtual public engagement — which came with its own set of challenges, but also returned major benefits — the data makes a strong case for continuing virtual proceedings.

Whether for ongoing health concerns or for the benefits to government decision-making, the evidence is clear: given the opportunity to participate virtually, the public will attend and in larger numbers than in person.

It’s understandable that elected officials have expressed a desire to return to in-person meetings for the face-to-face experience. However, successful virtual engagement has made an impressive impact as a way for governments to engage a larger and more diverse segment of their population.

Governments should not consider in-person or virtual meetings as an either/or decision. Instead, utilizing both methods in a hybrid model is a highly effective way to meet or exceed public information and communication objectives.

A New Era of Unified Public Engagement

Virtual public meetings are part of a new era of public engagement. Many state legislatures have recognized the benefits and have passed new laws allowing policies for continuing virtual public meetings to complement or supplant in-person meetings.

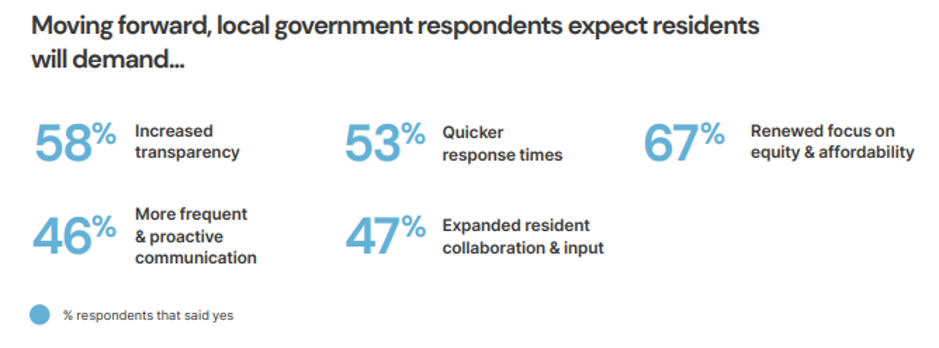

A recent survey from The Atlas, Engaging Local Government Leaders (ELGL), CivicPulse, CivicPlus, and Route Fifty reports 53% of responding jurisdictions that used virtual public meetings last year will continue to use them. Greater use of information technology by local governments over the last year has also increased expectations among residents for greater communication and information sharing with their governing bodies.

Click the image to view the “New Normal” survey report.

While the rise in COVID-19 cases should cause widespread alarm and a reexamination of public health policies in every state, governments are not facing the same great wall as they were in March 2020 when public communication and information processes came to a standstill. Proven options are available with virtual deliberations.

In Florida, the Treasure Coast newspaper editorial board has called on their county government to reinstate Zoom meetings permanently due to the increase in COVID-19 outbreaks and based on the fact virtual meetings facilitate greater public participation in government. The paper’s editorial stated:

Local governments around the state should not be looking to deep-six Zoom or any other video conferencing program they’ve used during the pandemic. They ought to be looking for ways to permanently integrate the services into the governing process. Zoom video conferences and Zoom commenting should be standard additions to the way local governments do business. Editorial Board – Treasure Cost Newspapers

The Cracks in Most Virtual Public Meetings Revealed by COVID-19

(This article was originally posted as a guest blog for PublicInput during Sunshine Week 2021)

Every state has open government laws regarding requirements and policies for public records and public meetings. A year ago, during Sunshine Week 2020, most states enacted emergency orders to rescind those laws due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For state and local governments, in particular, agencies and personnel were faced with an unprecedented challenge to manage operations remotely including their public engagement.

Access to and management of public records and public meetings became a major challenge for the public sector as well as for the public. Bringing together public officials virtually had its own challenges –technical and procedural. However, when it came to ensuring the public would be able to participate in those meetings, chaos emerged.

Technology is supposed to create efficiencies for its users. However, in many cases, virtual public meetings required more staff than conventional public meetings and from agencies that typically do not play a major role in these meetings.

Digital transition and adoption by government have lagged behind the private sector. For two decades, that focus has been prioritized on government’s transactional relationships with the public, e.g., (taking and processing payments, documentation, information searches, and exchanges) and less on interactional relationships, i.e., public engagement, even though end-to-end solutions are available. And the pandemic exposed these shortcomings in a big way.

As the government scrambled to comply with their legal requirements to ensure public and press access to public meetings, we saw three models of virtual public meetings emerge:

- Fail: Many jurisdictions wanted to forego all compliance with their open government laws regarding: records and meetings. And many decided not to make the effort if it wasn’t required, and if it was, performed the very basic response to meet the minimum requirements. Lacking the technology capabilities, the training, or just the initiative, the results were poor and unproductive leaving both the government bodies and the public with a lousy experience. Losing the public wasn’t the only consequence. Losing their trust at a critical time during a pandemic is something not easily regained.

- Frankenstein: This model emerged from most governments that made efforts to comply with laws and procedures by piecing together multiple technology solutions to handle the tasks. Think about an orchestra: many instrument sections to perform one musical piece. As Miami’s CIO, Mike Sarasti said on Twitter after a March 25 commission meeting, they “used @zoom_us for in-meeting participants, then attendee view was sent out to usual @Granicus, Twitter, FB Feeds. @Qualtrics for Form-based feedback, voicemail via @Cisco setup, @WeTransfer for vid submission. Add a fair share of talented co-workers, & you’re good.” That’s a lot of government cooks in the kitchen. This model is proving unsustainable due to its inefficiency, expense, and unpredictability.

- Future: This model represents those governments and agencies that realized and took advantage of end-to-end technology solutions specifically created to manage virtual public meetings/engagement and meet their legal and political responsibilities (like other GovTech solutions developed to handle different administrative responsibilities and requirements in other agencies). Benefits have included increased participation and inclusion, more manageable public input, greater efficiency and productivity, and trust.

One thing we have learned from successful virtual meetings over the last year is that given the opportunity to participate, the public will. However, the quality of the experience will determine whether they return.

Virtual meetings, when working, are being accepted by the public and by the public institutions convening them. Many public officials (especially elected ones) have expressed their desire to return to in-person meetings for that face-to-face experience. However, successful virtual public meetings have made an impressive impact as a way for governments to engage the public and vice versa.

An early concern in the pandemic was that due to the turmoil being created by virtual public meetings, once the virus subsided, governments would return exclusively to in-person meetings, missing the opportunity to create a new era of public engagement. However, that is not happening. New policies and laws are being changed or created to include the continuation of virtual public meetings that can complement or be held in lieu of in-person meetings.

In Boston, efforts are underway to make remote, virtual participation in public hearings and meetings a permanent fixture of city government. Legislation proposed in Nebraska will allow local governments to hold meetings via “virtual conferencing.” Similar efforts are being pushed in South Carolina and other states and local jurisdictions.

An engaged and informed public has economic and civic benefits, and virtual public meetings meet new communication and information needs and expectations of constituents.

The opportunity for governments will be how to structure their public participation to continue virtual public meetings and combine them with in-person meetings as they continue their transition in the digital age of public engagement and democratic practices.

Think of the virtual public meeting as the heart of citizen engagement.

Former Washington State representative Renee Radcliff Sinclair speaking about government transparency and trust said this week: “The COVID-19 pandemic has tested us all in ways we never imagined. And while its long-term societal impacts probably won’t be known for some time, in the short term it has substantially eroded our trust in our cornerstone institutions, including government… So, the question becomes, how do we build back that trust? By giving the public a front-row seat to its proceedings.”

January 6, 2021 and its Impact on Trust

Our nation is exceptionally troubled about the events that occurred on January 6 in the nation’s capital. The subsequent fallout is spreading beyond the crime scene and having a substantial impact including a growing suppression of online (free) speech.

The move by many private social media companies to remove content and participants from their online platforms will add another facet and challenge to a movement that’s been underway by journalism and pro-democracy groups and their related philanthropies to improve trust in media and in democracy in the U.S. Much of their work centers on reforms that address the creation and spread of misinformation and their sources. The recent actions by social media companies to remove inflammatory speech and their creators from their online platforms is an attempt to avert further violence blamed on the spread of misinformation and lies — most of it targeting the media and the government.

January 6 was the flash point and wake-up call to take this practice as a serious societal threat. However, suppression of free expression is also a threat to society. Those whose political ideologies fall on the right are feeling victimized by the actions of these companies to censor their online speech and conversations. For those whose ideologies lean left, while they may applaud the redaction, they need to understand the consequences. Both sides have valid reasons for concern.

While most of us did not foresee an assault on the nation’s capital, we have seen indicators in the inflammatory rhetoric and growing polarization occurring within government and among the public that has dramatically increased (but did not originate) with the election of President Trump.

No one can accurately say how this is going to end. But we see where it is heading. And the negative impact of the actions being taken is dangerous. For example, we know what results from suppressing conversations on mainstream social networks where different ideological points of view are common. Those whose opinions and comments are suppressed retreat to other social networks where contrary points of view are all but absent in these filter bubbles where the conversations are more extreme and the participants are more radical. This is not what we want and certainly not a way to bring folks with different opinions together.

The historical public square and the openness of public meetings by our governing institutions were designed intentionally to allow broad public participation in conversations and decisions about issues that affected the whole. Today, the public square is digital, having been taken over by private companies whose priority is to pursue profit, not democracy, which makes sense. However, their platforms are being utilized by both the public and their government institutions to serve as forums for political and policy discussions.

Unfortunately, governments still struggle to replicate the important components of our democracy (public comment and free expression) as they transitioned to the Internet. The broken promise of “Gov 2.0” has been the failure to bridge the chasm between the electors and the electorate that it touted would occur online by improving communication and information sharing and consequently, our democracy.

Instead, private companies, lacking the guardrails that the government operates with, assumed a facilitator role not by design but by default and the potential for revenue. Key components important to ensure informed and engaged dialog like attribution and validation were replaced by anonymity and disparagement. They are called “social” networks for a reason.

We can’t fall back to our bunkers. We have to have more conversations that include representatives from the public, press, and public sector, with support from the GovTech community to collaborate on the many complex challenges. I read a recent blog that stated “…when it comes to building trust, there are no home runs, doubles, or triples — just countless sacrifice bunts.” The change will be incremental, but it can happen. What occurred on January 6th in D.C. has added more urgency and increased the odds of rebuilding trust in our democracy, our news media, and in others.

From Bad Bills Come Bad Laws: A Proactive Prescription for Restoring Trust in Government and Democracy

When the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation announced in March a $300 million investment to improve the quality of local news, it made an important first step to restoring trust in a key component of our society.

The funding decision was spurred by a recent report from the Knight Commission on Trust, Media and Democracy, which explored the disconnect between the public, the press, and our public institutions, notably the government.

Its conclusion: We are in a watershed moment and must make reforms in our media and civic infrastructure.

The report advances a series of recommendations aimed at the news media, civic educators, and the public. And while the report urges “every government official to be open and transparent,” what is missing is a list of reforms required in our federal, state, and local governments to help restore trust.

Instructing government to be transparent is not enough. Restoring trust in democracy through our public institutions must include reforms in all branches to ensure openness, access and accountability.

Knight addresses one area of needed reforms by granting $10 million to the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press to increase litigation efforts to defend access to public information. This is an important and welcome investment to ensure our First Amendment rights.

Even so, building trust in government requires a strong offense as well as a strong defense. The National Freedom of Information Coalition and its state coalitions support a multi-faceted approach beyond reactionary litigation to usher in needed reforms.

Most litigation challenges bad laws that lead to bad policies. But before they were bad laws, they were bad bills. A proactive, holistic approach to needed legislative and policy reforms can prevent these bad laws and poor public policies from being created in the first place.

It’s a daunting task to enact reforms that promote trust in our public institutions in an era where more and more governments, particularly state legislatures, attempt to undermine existing open government precedent, making it harder for journalists and the public to monitor and report violations that diminish access and accountability.

But there are areas that have shown results to increase transparency and accountability of our public institutions and should be instilled in all public institutions across the nation:

· Legislative tracking. Bad bills can be identified and fought early. Yet this is not an easy task. Many state legislatures can bury amendments that dismantle existing open government laws or increase exemptions to existing laws in the text of unrelated bills — hiding them from the public until it’s too late.

· Compliance enforcement. State and local governments across the nation inconsistently comply with their open government laws. Sometimes it’s a lack of training and education. Other times it’s intentional. Enforcement of existing open government laws is critical to discourage violations. Yet violators are rarely charged and when they are, punishment is usually a slap on the wrist.

· Formal appeals processes. Some states don’t have an appeals process when a record is denied, leaving the petitioner no option but to sue, which creates a financial burden not only on the requestor but also on the taxpayer. Independent state open records ombudspersons are a way some states combat this issue. Fee shifting, where the losing government agency pays the legal fees of the prevailing petitioner is another.

· Technology solutions. Open data and online request portals readily provide public access to public records, establish or advance professional standards, and help create best practices within executive branch agencies.

Without public oversight, without creating more professionalism in administering state open government laws and policies, and without an internal culture to punish violators, there will always be inevitable situations where a bad bill is passed, or when a public agency continues to deny access in violation of their state open government laws. And the only option is to sue.

Still, through enacting reforms in all branches of state and local governments, and proactively monitoring and educating the public (and officials of their responsibilities), we can help restore trust in our democracy by restoring trust in our public institutions.

Daniel Bevarly is executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that promotes press freedom and legislative and administrative reforms that ensure open, transparent, and accessible state and local governments. Reach him at dbevarly@nfoic.org.

With cybersecurity hot, now is the time to open government

This article originally appeared in STATESCOOP

Commentary: Opening data isn’t at odds with IT security, but supports it, says the executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition.

With governments focused on tighter security measures surrounding sensitive data, now is an opportune time to adopt reforms that also remove obstacles to open public records and improve access.

Updating open government laws, and reforming policies and practices can yield numerous benefits — economic and political — and free resources to focus on malicious cyberattacks and ongoing data security.

State and local governments face a real threat from hackers infiltrating government IT systems and accessing personal and sensitive information. State CIOs, once again, identified security as their top priority in the National Association of State Chief Information Officers’ Top Ten list for 2019.

However, the government must provide ongoing access to public records that is distinct from its responsibility to prevent illegal access to private information.

The best way to enact reforms is for government to take a holistic approach to the way public institutions manage transparency and public records. With better legislation and administrative guidelines, agencies can vastly improve access to public records and meet the growing challenge of digital public records as they are created. Here are four ways to make government more open:

- Disclose proactively

This is the act of releasing information before it is requested (or shortly after it is). Public records such as meeting minutes, reports, schedules, and data sets can be posted to an agency’s website or centralized in a designated online public records repository. The source can be a government server or one managed by an external third party through cloud services, as cited in the NASCIO survey to address growing data storage.

- Improve training and education

Time is money. So are costs associated with litigation which, unfortunately, is sometimes the result of poor FOI administration. Better and ongoing training and education of employees can increase agency efficiency and lower admin costs.

- Adopt professional standards and best practices

Fulfilling open records requests is a daily task. However, most agencies treat public records requests as a distraction or an “add-on” to their programs and services. Developing behaviors to increase proficiency and decrease expenses can be replicated in other agencies, such as tracking time and costs to process requests and maintaining a log of agency responses.

- Change the culture

Advance an internal mindset that addresses open records fulfillment as a public service responsibility, not a distraction. Quantify it as a line item on the budget. After all, it is the law.

Viewing their role as a steward and facilitator, government agencies can secure public information without restricting it. This creates both financial and political benefits by increasing responsiveness, accountability, and trust while focusing more resources on securing protected information.

Solving the “Civic Infrastructure” Challenge through Innovation

The Knight Foundation is responsible for bringing together 100 civic innovators from across the country to Miami this week to “tackle some of the thorniest questions on the future of cities.” Dubbed the “Civic Innovation in Action Studio,” Knight hopes to “develop a set of investment-worthy experiments that will be piloted in communities” to tackle challenges around harnessing talent, advancing opportunity and increasing engagement.

The Knight Foundation is responsible for bringing together 100 civic innovators from across the country to Miami this week to “tackle some of the thorniest questions on the future of cities.” Dubbed the “Civic Innovation in Action Studio,” Knight hopes to “develop a set of investment-worthy experiments that will be piloted in communities” to tackle challenges around harnessing talent, advancing opportunity and increasing engagement.

Most of these challenges surround the strength and quality of a community’s civic infrastructure. Civic Infrastructure has been defined as “the foundation for our democracy” and “the mechanism where key community stakeholders can address systemic problems and work towards solutions.” It’s also been defined as the system of “social connections, decision-making processes, difficult conversations and informal networks that influence how the people in a community function.”

Suffice it to say there is enough substance within these definitions to establish a sense of organization and purpose for what constitutes a civic infrastructure. Other descriptions may touch on the soul, vibe or rhythm of the social and economic connectivity within a community. What we are looking at is whether its presence is strong or weak and whether it is deeply rooted in a community or a mere veneer that exists only in terminology.

The Knight Foundation and its “civic innovator participants” will wrestle not only with answers for solutions but also with questions surrounding the challenges.

“Civics” and “citizenship” are common terms that will be tossed about during this three day event. These terms have enjoyed a long history and tradition in our nation and communities. However, our nation and its cities have transformed and it’s time we reconsider what those terms mean in today’s society and economy.

We also have to reexamine society’s role and its different components in these areas. What is the role of government and the public sector? How has public policy impacted communities? What is the role of citizens (now more appropriately identified as “residents”)? How has diversification within society and income levels impacted communities? What is the role of the private sector? Has private resources or lack thereof had an impact on communities?

What about new challenges from sweeping changes in communication and information sharing technologies? And just as equally, how can these changes help address and devise solutions?

I don’t believe anyone expects a silver bullet to come from these short proceedings this week in Miami. Societal changes are incremental no matter how fast and expansive information travels and personal connectivity can occur today. I’d settle for a couple of “A-ha” moments that give direction to further exploration, which, I suspect Knight is seeking as it continues its admirable investment to improve America’s civic infrastructure.

Embracing Incrementalism: Open Data program managers need excellent peripheral vision

I recently delved into Mark Headd’s insightful blog post, “Don’t Hang Any Pictures,” where he imparts wisdom to those steering open data programs in local governments. He provides a practical list of “Do’s” and “Don’ts,” serving as a compass for smoother and more successful project implementation. As the title suggests, his central advice revolves around avoiding complacency. I’ll add another one: Incrementalism (think tortoise in the “Tortoise and the Hare.)”

In my 13 years of experience within local government, coupled with a career in public administration, I’ve come to recognize the significance of incrementalism. It’s not just a strategy; it’s a way of life within the governmental realm. You can push or pull as much and as hard as you like, but there will be limits in all directions no matter how determined or how gifted you are. Why do you think they call the government an “institution?” Regardless of determination or skill, pushing or pulling too hard encounters limitations inherent in the bureaucratic nature of government.

Moving in increments frustrates public administrators, legislators, and citizens. And it’s also deeply woven into the fabric of our democracy. The tension between the desire for swift change and the reality of incremental progress has been a defining characteristic of our government.

While some embrace incrementalism as a key to a successful public sector career, others resist or revolt, leading to premature exits from government service. Others, still, adopt the bureaucratic characteristic of incrementalism to piece together complacent, yet lack-luster careers in government characterized by lowered expectations and initiative, and a don’t-rock-the-boat mentality.

Elected officials face an additional layer of complexity, given the limited timeframe of their terms. Major initiatives, such as community revitalization projects, often span multiple administrations, demanding strategic planning to ensure continuity and dedicated resources over an extended period.

Integrating communication and information technology into government projects, particularly initiatives like opening data to the public, has to be the greatest challenge. Capping the speed and flexibility of electronic information and communication and applying rigid, even restrictive guidelines to its access and content in an environment known for moving slowly.

This challenge is keenly felt by CIOs, CDOs, and MIS professionals tasked with open data initiatives, facing the delicate balance of moving at the right pace, which may not always align with the elected officials’ or the public’s expectations.

Doug Robinson, the director of NASCIO, a boutique national organization of state and territory government CIOS, can attest to the ever-changing landscape of senior leadership positions within top IT positions. The turnover within this role is unparalleled, reflecting the dynamic nature of the challenges they confront.

Headd’s advice to “not get comfortable” and to recognize the temporary nature of public service is a sad reminder. While this may be true in certain cases, government IT professionals should not assume that short tenures are inevitable. Success in one administration can lead to opportunities in another, presenting an opportunity to contribute their knowledge and expertise to new open data challenges.

In conclusion, embracing incrementalism is not a concession to inefficiency but a pragmatic acknowledgment of the intricacies within the governmental machinery. It requires a delicate balance between pushing for progress and respecting the established processes, ensuring that the journey towards open data initiatives is both sustainable and impactful.